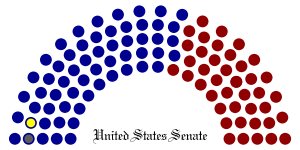

International Parliamentary Union Right of minority representation in legislative bodiesImage via Wikipedia

Right of minority representation in legislative bodiesImage via Wikipedia

By Rey Cartojano Right of minority representation in legislative bodiesImage via Wikipedia

Right of minority representation in legislative bodiesImage via WikipediaAfter partisan politics was supposed to be settled in the last May 10 elections, the next order of the day especially for local officials is the process of formulating and passing ordinances and other legislative work.

Section 50 of the Local Government Code sets the tone of this process by requiring the concerned legislative body, or Sanggunian, to adopt or update its existing internal rules of procedure starting its first regular session and within ninety (90) days thereafter. The adoption or updating of the internal rules of procedure is a critical process in local legislative work as it prescribes assignments in chairmanships and memberships of committees where most legislative work take place. In addition, the internal rules of procedure can decisively prescribe the manner on how local legislative business will be conducted especially to favor the dominant political party or grouping.

A question of controversial impression is whether the internal rules of procedure can prescribe the process of appointments of committee chairmanships and memberships to favor only a dominant political party or grouping. Stated directly, is it legal and in accordance with parliamentary practice to limit chairmanship and membership of all committees to the members of a dominant political party?

In answering queries for legal opinions especially covering issues in the interpretation of internal rules of procedures, the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) has always outlined the hierarchy of sources of authorities as follows: (1) 1987 Constitution; (2) Laws, especially the Local Government Code; (3) Court decisions; (4) Internal Rules of Procedures of the concerned Sanggunian; and (5) Parliamentary customs, usage and authors.

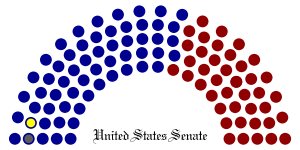

Suffice it to state at this stage that in international parliamentary customs and usage, and even bolstered by multitude of scholars and authors, the rule is settled that in a parliamentary set-up working through many committees, apportionment of committee chairmanships and memberships is allocated in proportion to the percentage of minority representatives vis-a-vis the total elected representatives. In fact, this formula is even followed by the present Philippine Congress in the distribution of committee assignments, which means that a congressman coming from minority parties and groups is always assured of a committee assignment, with or without him asking for it.

If we follow the hierarchy of authorities stated in many DILG legal opinions, it seems that minority representation in local legislative committees is doomed if the internal rules of procedure will favor committee appointments of chairmen and members highly dependent on the will of the majority, as the Philippine Constitution, laws and court decisions which are supposed to occupy higher level of authorities on the matter on minority representation do not yet have a clear coverage and resolution.

However, the International Parliamentary Union (IPU), a global organization of various state parliaments of which the Philippines is a member, cited Article 25 of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights, which the Philippines ratified last 1986, on the right of the citizens to be heard through their elected representatives. The right of the citizens to be heard through their elected representatives is interpreted to include the right of the said representatives to be given fair representation in parliamentary committees, which almost all parliaments in the world already are adopting.

By the doctrine of incorporation found in Article 2, Section 2 of the 1987 Constitution (where the Philippines adopts by incorporation international laws as part of our domestic laws), the International Convention on Civil and Political is already part and parcel of the laws of the land. As such, then, it is submitted that any internal rules of procedure of any local legislative assembly in the Philippines which infringe on the right of minority political groups to be represented in parliamentary committees, for that matter, is not only illegal but not in accordance with internationally accepted parliamentary customs and practices.

At the end of the day, representative democracy is not all about what the majority wills government to be as it is about giving the right of other elected representatives to be heard, participate and check the process of legislation.